Please select your Class

|

MARSHALL ALMA MATER

Patriots arise! Be Loyal, strong, and true; And lift your colors to the sky, The red, the white, and the blue. Your sons and daughters stand With pride throughout the land. Hail Alma Mater! John Marshall High MARSHALL FIGHT SONG Fight on you Patriots Win for Marshall tonight, Score up a victory Charge with all your might (Fight,Fight,Fight). Fight on you Patriots for our red, white, and blue Go Marshall all the way, We're all for you. |

John Marshall High School

Alumni Association

Indianapolis, Indiana

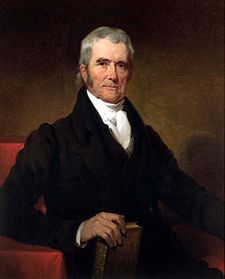

Namesake

================================================================| Answers.com |

John Marshall, U.S. Supreme Court Justice / Jurist

John Marshall was the fourth Chief Justice of the United States, appointed in 1801 by President John Adams. In the 34 years that Marshall presided over the Supreme Court, the federal powers of the judicial branch were defined and strengthened, most notably in the 1803 case of Marbury v. Madison, in which Marshall asserted the power of the court to overturn legislation deemed unconstitutional. Marshall grew up in Virginia and practiced law before getting involved in Federalist politics. Adams appointed him to be an envoy to France during the XYZ Affair (1797), then tried to appoint him to the court. Marshall refused and instead served in the House of Representatives (1799) before Adams named him secretary of state (1800) and then Chief Justice (1801). Politically, Marshall was famously at odds with his distant cousin, Thomas Jefferson, especially during the trial of Aaron Burr (1807), when the strength of the court was pitted against the strength of the executive branch. Burr, on trial for treason, was acquitted after Marshall ruled that two witnesses were needed prove the charge. Marshall's long term on the bench occurred at a time when the newly-formed nation was still taking shape, and he is considered one of the most influential jurists in U.S. history. Marshall, who had been a captain in the Revolutionary War, authored a five-volume biography of George Washington, his commander at Valley Forge.

(born Sept. 24, 1755, near Germantown, Va. — died July 6, 1835, Philadelphia, Pa., U.S.) U.S. patriot, politician, and

jurist. In 1775 he joined a regiment of minutemen and served as a lieutenant under Gen. George Washington in the American

Revolution. After his discharge (1781), he served in the Virginia legislature and on Virginia's executive council (1782 – 95),

gaining a reputation as a leading Federalist. He supported ratification of the U.S. Constitution at the state's ratifying

convention. He was one of three commissioners sent to France in 1797 – 98 (see XYZ Affair); he later served as

secretary of state (1800 – 01) under Pres. John Adams. In 1801 Adams named Marshall chief justice of the Supreme Court of

the United States, a post he held until his death. He participated in more than 1,000 decisions, writing 519 himself. During his

tenure, the Supreme Court set forth the main structure of the government; its groundbreaking decisions included

Marbury v. Madison, which established judicial review; McCulloch v.

Maryland, which affirmed the constitutional doctrine of "implied powers"; the Dartmouth College case,

which protected businesses and corporations from much government regulation; and Gibbons v. Ogden,

which established that states cannot interfere with Congress's right to regulate commerce. Marshall is remembered as the principal

founder of the U.S. system of constitutional law.

(b. Germantown [now Midland], Va., 24 Sept. 1755; d. Philadelphia, Pa., 6 July 1835; interred New Burying Ground, Richmond, Va.),

chief justice, 1801-1835. By common acclaim, John Marshall is "the great Chief Justice," the single best representative of American

constitutional law. His greatness, as Oliver Wendell Holmes noted in 1901, consisted partly in his "being there" during the

formative period of the Court's history. But Marshall's conservative?national ideology fit the formative age perfectly, just as his

personality and legal genius exactly suited the duties of chief justice. Bibliography

As the fourth chief justice of the United States, John Marshall (1755-1835) was the principal architect in consolidating and defining the powers of the Supreme Court. Perhaps more than any other man he set the prevailing tone of American constitutional law. The eldest of Thomas and Mary Marshall's 15 children, John Marshall was born on Sept. 24, 1755, near Germantown, Va. Frontier and family were the shaping forces of his youth. His mother came from the aristocratic Randolphs of "Turkey Island." His father - "the foundation of all my own success in life," recalled John Marshall - was a man of humble origin who, through native ability and strength of character, rose to relative prominence. Marshall's spare formal education consisted mainly of tutored lessons in the classics and Latin. His father saw to it, however, that John was solidly grounded in English literature and history; he also brought home practical lessons in politics from his service in the Virginia House of Burgesses during the years preceding the American Revolution. Family unity, a tradition of learning, and a concern for affairs of the world shielded young Marshall from the barbarity of the frontier. But the West also left its mark - in a gaiety of heart, an open democratic demeanor, and a manliness of character that were no small part of Marshall's gift of leadership. American Revolution A dedicated patriot from the outset, Marshall saw action with the Culpepper Minutemen in 1775. As an officer in the Continental Line, he took part in several important battles and endured the hardships of Valley Forge. His experience, fortified by his association with George Washington and other nationalist leaders, left him with the passionate love of union and chronic distrust of state particularism that later became the twin pillars of his constitutional law. Before Capt. Marshall was mustered out of the Army in 1781, he had decided on law as a profession. He heard George Wythe's law lectures at the College of William and Mary in 1780, and during that summer he was licensed to practice and that August was admitted to the county bar. During this same period Marshall fell in love with Mary Ambler. They were married in January 1783 and took up residence in Richmond, Va. Early Political Career Marshall's natural eloquence, charismatic personality, and rare gift for logical analysis overcame the deficiencies in his legal education. He rose quickly to the head of the Richmond bar. He also distinguished himself in state politics. He sat in the House of Burgesses (1782-1784, 1787-1791, and 1795-1797), where he consistently supported nationalist measures. He served on the important Committee on the Courts of Justice and when only 27 was elected by the legislature to the governor's Council of State. Marshall's legislative experience confirmed his belief that the Articles of Confederation needed to be strengthened against the irresponsible and selfish forces of state power. As a delegate to the Virginia convention for the ratification of the Federal Constitution (1788), he put his nationalist ideas to use. Though somewhat overshadowed by established statesmen, he spoke influentially for ratification. And on the hotly debated subject of the Federal judiciary, he led the nationalist offensive. Federalist orthodoxy and demonstrated ability soon won Marshall national prominence. During the crisis over the Jay Treaty in 1795, when party lines began to crystallize, Marshall supported Washington and Alexander Hamilton against the Jeffersonian Republicans. As a lawyer in the Supreme Court case of Ware v. Hylton (1796), he adhered to Federalist principles by arguing the supremacy of national law. Marshall had turned down offers from President Washington to be attorney general and minister to France. In 1797 he agreed to serve on the "XYZ mission" to France. Shortly after his return, President John Adams offered him an appointment to the Supreme Court, but he declined. Elected to Congress in 1798, he soon became a leader of the Federalists in the House. Declining to serve as secretary of war, he accepted appointment in 1800 as secretary of state. Eight months later Adams appointed him chief justice of the Supreme Court, hoping to hold back the forces of states'-rights democracy, which in the form of the Jeffersonian Republicans had gained control of the Federal government. Chief Justice Marshall took his seat on the Court on March 5, 1801, and from that time until his death was absorbed in judicial duties. He did find time, however, to write a five-volume biography of George Washington (1804-1807) and to serve in the Virginia constitutional convention (1829-1830). But it was as chief justice that Marshall made his mark on American history. The pressing problem in 1801 was to unify and strengthen the Court. Accordingly he persuaded his colleagues to abandon the practice of delivering separate opinions and to permit him to write the opinion of the Court, which he did in the great majority of cases from 1801 to 1811. In addition, Marshall gave the Court a needed victory. His opinion in Marbury v. Madison (1803) for the first time declared an act of Congress unconstitutional, thus consolidating the Court's power of judicial review and providing future Courts with an elaborate defense of judicial power. In United States v. Peters (1809) Marshall struck another blow for judicial power, this time against the claims of a state, by establishing the Court's right to be the final interpreter of Federal law. His opinion in Fletcher v. Peck held that the contract clause of the Constitution prevented state legislatures from repealing grants of land to private-interest groups. This was the first in a series of contract decisions that encouraged the growth of corporate capitalism. Few of Marshall's opinions touched civil rights; but in the Aaron Burr treason case, he struck a powerful blow for political freedom by defining treason narrowly and requiring strict proof for conviction. Precedent-setting Cases From the end of the War of 1812 through 1824 the Marshall Court was most creative. Marshall's position on the Court was less dominant than it had been before because able, new justices appeared. But he was unquestionably the guiding spirit and personally wrote opinions in the most important constitutional cases. Two such were McCulloch v. Maryland (1819) and Gibbons v. Ogden (1824). In the first case, Marshall upheld the congressional act chartering the Second Bank of the United States, thereby securing a national currency and credit structure for interstate capitalism. Also, by authorizing Congress to go beyond enumerated powers through a broad interpretation of the "necessary and proper" clause, he created a body of implied national powers. Marshall's Gibbons opinion gave Congress supreme and comprehensive authority within the enumerated powers of Article I, Section 8, of the Constitution. The definition of commerce in the Gibbons case was sufficiently broad to bring the revolutionary developments in transportation and communication of the 20th century within the scope of congressional authority. These two cases created a reservoir of national power and guaranteed a flexible Constitution that could meet the nation's changing needs. That the Court should be the final interpreter of that flexible Constitution was the message of Marshall's compelling opinion in Cohens v. Virginia (1821). Marshall's Concept of the Nation Nationalist though he was, Marshall did not intend to destroy the states or establish the nation as an end in itself. He envisaged the national good as the sum of the productive individuals who constituted it, each pursuing his self-interest. Accordingly Marshall's opinions worked to release the creative energies of private enterprise and create a national arena for their operation. In Dartmouth College v. Woodward (1819) Marshall ruled that a corporation charter was a contract within the meaning of the Constitution which the states could not impair. As a result, private educational institutions, along with hundreds of business corporations chartered by the states, were secured against state interference. The unleashed forces of commerce, Marshall believed, would transcend selfish provincialism and create a powerful, self-sufficient nation. Aroused states'-rights pressures in the 1820s forced the Marshall Court to curtail its nationalism. In addition, new appointments to the Court allowed division and dissent to burst into the open. The chief justice did not surrender national principles - as evidenced in Brown v. Maryland (1827) and Worcester v. Georgia (1832) - and he continued to lead the Court, but the age of judicial creativity was temporarily over. With the election of President Andrew Jackson in 1828, Marshall became increasingly pessimistic. Meanwhile the death of Marshall's wife left him disconsolate. And his own health began to fail, though he remained intellectually alert and continued performing his duties until his death on July 6, 1835. Marshall died believing that the Constitution and the republic for which he had labored were gone, but history proved him wrong. The nation continued along the course of nationalism and capitalism that he had done so much to establish; the Court and the law continued to follow the lines he projected. His reputation as the "great chief justice" seems secure. Further Reading Albert J. Beveridge, The Life of John Marshall (4 vols., 1916-1919; rev. ed., 2 vols., 1947), despite its nationalist bias, remains the standard biography. Edward S. Corwin, John Marshall and the Constitution: A Chronicle of the Supreme Court (1919), concentrates on his judicial career. James Bradley Thayer and others, John Marshall (1967), is a collection of classic essays. William M. Jones, ed., Chief Justice John Marshall: A Reappraisal (1956), is another collection of distinguished essays. The most exhaustive analysis of Marshall's judicial philosophy is Robert K. Faulkner, The Jurisprudence of John Marshall (1968). The relationship between the two giants of American constitutional development is examined in Samuel J. Konefsky, John Marshall and Alexander Hamilton: Architects of the American Constitution (1964). Standard constitutional histories, such as Charles Warren, The Supreme Court in United States History (3 vols., 1923; rev. ed., 2 vols., 1926), and Charles G. Haines, The Role of the Supreme Court in American Government and Politics, 1789-1835 (1944), also contain material on Marshall's career. For further material the reader should consult James A. Servies, A Bibliography of John Marshall (1956), and numerous essays on him in historical and legal periodicals.

Born: Sept. 24, 1755, Germantown, Va. See also Cohens v. Virginia; Dartmouth College v. Woodward; Fletcher v. Peck; Judicial review; Marbury v. Madison; McCulloch v. Maryland Sources

(1755-1835), chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. Marshall, who had almost no formal schooling and studied law for only six weeks, nevertheless remains the only judge in American history whose distinction as a statesman derived almost entirely from his judicial career. Combat experience during the Revolution helped him develop a continental viewpoint. After admission to the bar in 1780, he entered the Virginia assembly and rose rapidly in state politics. He had good looks, a charismatic personality, and a debater's gifts. A Federalist in politics, he championed the Constitution in his state's ratification convention. Following a diplomatic mission to France, he won election to Congress, where he supported President John Adams. Adams appointed him secretary of state and in 1801 chief justice, a position he held until death. John Jay, the first chief justice, who had resigned, described the Court as lacking "weight" and "respect." After Marshall no one could make that complaint. In 1801 he and his colleagues had to meet in a tiny room in the basement of the Capitol because the planners of Washington, D.C., had forgotten to provide space for the Supreme Court. Marshall made the Court a prestigious, coordinate branch of the government. In 1824 Senator Martin Van Buren, a political enemy, conceded that the Court attracted "idolatry" and its chief was admired "as the ablest Judge now sitting upon any judicial bench in the world." During Marshall's thirty-four years as chief justice, he gave content to the Constitution's comissions, clarified its ambiguities, and added breathtaking sweep to the powers it conferred. He set the Court on a course for "ages to come" that would make the U.S. government supreme in the federal system and the Court the Constitution's expositor. He acted as if he were the enduring Framer whose constituency was the nation; he knew the true meaning of the Constitution and he meant it to prevail; he made his position a judicial pulpit to foster the Union of his dreams and to compete, if possible, with the political branches in shaping public opinion and national policy. Marshall's judicial energies were as indefatigable as his vision was broad. Although he cast but a single vote and was eventually surrounded by colleagues appointed by a party he deplored, he dominated the Court as no one has since. He scrapped seriatim opinions in favor of a single "opinion of the Court" and during his long tenure wrote nearly half the Court's opinions in all fields of law and two-thirds of those involving constitutional questions. He exercised judicial review, firmly over state statutes and state courts, prudently over acts of Congress. Marbury v. Madison (1803) remains the fundamental case. Marshall read principles of vested rights into the contract clause and expanded the Court's jurisdiction. Notwithstanding judicial rhetoric conjuring up the bugles of Valley Forge, his judicial nationalism, which was real enough and helped emancipate American commerce in Gibbons v. Ogden (1824), sometimes constituted a guise to block regulatory state legislation that limited property rights. He linked the Constitution with national supremacy, capitalism, and judicial review.

Bibliography:

Early Life The eldest of 15 children, John Marshall was born in a log cabin on the Virginia frontier (today in Fauquier co., Va.) and spent his childhood and youth in primitive surroundings. His father rose to prominence in local and state politics. Through his mother he was related to the Lees and the Randolphs and to Thomas Jefferson, later his great antagonist. Marshall first left home for any length of time to serve as an officer in the American Revolution. He returned in 1779 after attending for a few months lectures on law given by George Wythe at the College of William and Mary (his only formal education). Admitted to the bar in 1780, he practiced law in the West and was elected (1782) a delegate to the Virginia assembly. He married and settled in Richmond, his home until his death. Political Career His brilliant skill in argument made him one of the most esteemed of the many great lawyers of Virginia. A defender of the new U.S. Constitution at the Virginia ratifying convention, Marshall later staunchly supported the Federalist administration, and after refusing Washington's offer to make him U.S. Attorney General or minister to France, he finally accepted appointment as one of the commissioners to France in the diplomatic dispute that ended in the XYZ Affair. Marshall's effectiveness there made him a popular figure, and he was elected to Congress as a Federalist in 1799. One of the tiny group that continued to support President John Adams, he was prevailed upon to become Secretary of State (1800- 1801). Before he left the cabinet he was appointed Chief Justice and confirmed by the Senate despite some opposition. Great Chief Justice> In his long service on the bench, Marshall raised the Supreme Court from an anomalous position in the federal scheme to power and majesty, and he molded the Constitution by the breadth and wisdom of his interpretation; he eminently deserves the appellation the Great Chief Justice. He dominated the court equally by his personality and his ability, and his achievements were made in spite of strong disagreements with Jefferson and later Presidents. A loyal Federalist, Marshall saw in the Constitution the instrument of national unity and federal power and the guarantee of the security of private property. He made incontrovertible the previously uncertain right of the Supreme Court to review federal and state laws and to pronounce final judgment on their constitutionality. He viewed the Constitution on the one hand as a precise document setting forth specific powers and on the other hand as a living instrument that should be broadly interpreted so as to give the federal government the means to act effectively within its limited sphere (see McCulloch v. Maryland). His opinion in the Dartmouth College Case was the most famous of those that dealt with the constitutional requirement of the inviolability of contract, another favorite theme with Marshall. His interpretation of the interstate commerce clause of the Constitution, most notably in Gibbons v. Ogden, made it a powerful extension of federal power at the expense of the states. In general Marshall opposed states' rights doctrines, and there were many criticisms advanced against him and against the increasing prestige of the Supreme Court. The sometimes undignified quarrel with Jefferson (which had one of its earliest expressions in Marbury v. Madison) reached a high point in the trial (1807) of Aaron Burr for treason. Marshall presided as circuit judge and interpreted the clause in the Constitution requiring proof of an "overt act" for conviction of treason so that Burr escaped conviction because he had engaged only in a conspiracy. Marshall's difficulties with President Jackson reached their peak when Marshall declared against Georgia in the matter of expelling the Cherokee, a decision that the state flouted. Influence and Style Marshall in his arguments drew much from his colleagues, especially his devoted adherent, Justice Joseph Story, and he was stimulated and inspired by the lawyers pleading before the court, among them some of the most brilliant legal minds America has seen, including Daniel Webster, Luther Martin, William Pinkney, William Wirt, and Jeremiah Mason. Marshall in his manners combined the unceremonious heartiness of the frontier with the leisurely grace of the Virginia aristocracy. So great was his winning charm and so absolute his integrity that he gained the admiration of his enemies and the unbounded affection of his friends. His style combined conciseness and precision. He wrote each opinion as a series of logical deductions from self-evident propositions, and it was almost never his practice to cite legal authority. It is in these opinions that his literary skill is shown rather than in his major nonlegal work, The Life of George Washington (5 vol., 1804-7). Marshall's constitutional opinions are collected in editions by J. M. Dillon (1903) and J. P. Cotton (1905). An autobiographic sketch was published in 1937. Bibliography

See biographies by

A public official of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Marshall served as chief justice of the Supreme Court

from 1801 to 1835. His interpretations of the Constitution in cases such as Marbury versus Madison served to

strengthen the power of the Court and the power of the federal government generally.

John Marshall presided over the U.S. Supreme Court from 1801 to 1835. Appointed by President John Adams, Marshall assumed leadership during a pivotal era. The early nineteenth century saw tremendous political battles over the future of the United States and its Constitution, often with the Court at the center of controversy. By the force of personality, argument, and shrewdness, Marshall steered it through this rocky yet formative period. He weathered harsh criticism as the Court set important precedents that increased its power and defined its role in government. Historians credit him with establishing what has been called the American judicial tradition, in which the Supreme Court acts as an independent branch of government endowed with final authority over constitutional interpretation. Marshall was born September 24, 1755, near Germantown (now Midland), Virginia. He was the son of Thomas Marshall, a wealthy landowner, justice of the peace, and sheriff. Like his father he fought in the Revolutionary War and married into a prominent family. His father's tutoring significantly enhanced his mere two years of formal education, which were augmented in 1780 by a brief attendance at lectures in law at the College of William and Mary. Marshall was also influenced by George Washington. Because of his service to General Washington in the war, Marshall became a strong Federalist. He later wrote about his mentor in his book Life of George Washington (1805-7). Marriage ties made Marshall a relative of a leading Virginia political family. This helped secure his place in society, paving the way for an early legal and political career in the 1780s. He specialized in appellate cases and quickly distinguished himself in the Virginia state bar. He also served in Virginia's council of state from 1782 to 1784, and in its house of delegates four times between 1782 and 1795. But it was as a partisan of the Federalists— the opponents of the states' rights-minded Republicans—that he came to wide acclaim. The struggle between the Federalists and the Jeffersonian Republicans was the most important political contest of the day. Marshall served as a devoted publicist and organizer for the Federalist cause in Virginia, and this work earned him various offers to serve as U.S. attorney general and as an associate justice of the Supreme Court. It also earned him the animosity of his distant cousin, Republican Thomas Jefferson, who soon became U.S. president and was his lifelong political adversary. In 1798 Marshall agreed to serve Federalist president John Adams as one of three U.S. ministers to France during one of the Napoleonic Wars between France and Great Britain. In a scandal known as the XYZ Affair, the French foreign ministry attempted to solicit a bribe from the U.S. emissaries, and Marshall became a national hero for refusing. He quickly emerged as the leading spokesman for Federalism in Washington, D.C., as a member of Congress from 1799 to 1800 and briefly as secretary of state under Adams in 1800. Then Adams lost the 1800 presidential election to Jefferson, and the Republicans won control of Congress. In a desperate attempt to preserve the Federalists' power, Adams spent the remaining days of his administration making judicial appointments. Sixteen new positions for judges on federal circuit courts and dozens for justices of the peace in the District of Columbia were handed out during the final days of Adams's administration. These last-minute appointees came to be known as midnightjudges. One of these seats went to Marshall, who was appointed chief justice of the Supreme Court. On March 4, 1801, Marshall assumed his duties as the head of the Court. Jefferson and the Republicans were furious over Adams's court stacking, and they swiftly quashed the appointments—except that, inexplicably, they did not challenge Marshall's. Marshall kept the Court out of the fray. He feared that in a conflict between the judiciary and the executivebranch, the Court would lose. Marshall again faced political conflict when in 1803 the Court ruled on a case brought by William Marbury, whose appointment as a D.C. justice of thepeace had been one of those barred by the Republicans. Marshall's opinion for the unanimous Court in Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 137, 2 L. Ed. 60, dismissed Marbury's suit on the ground that the Supreme Court lacked jurisdiction to rule on it. But at the same time, the Court restated the position that it had the power to rule on questions of constitutionality. By striking down a section of the Judiciary Act of 1789 (1 Stat. 73), Marshall's opinion marked the first time that the Court overturned an act of Congress. Not for more than fifty years would it exercise this power again. Marshall asserted the right of the Supreme Court to engage in judicial review of the law, writing, "It is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is." Marbury was the crucial first step in the evolution of the Supreme Court's authority as it exists today. Marshall emphasized the need to limit state power by asserting the primacy of the federal government over the states. In 1819, as Marshall reached the height of his influence, he cited the Contracts Clause of the U.S. Constitution (art.1, §10) as a basis for protecting corporate charters from state interference (Trustees of Dartmouth College v. Woodward, 17 U.S. [4 Wheat.] 518, 4 L. Ed. 629). That year he also struck a blow to states' rights in McCulloch v. Maryland, 17 U.S. (4 Wheat.) 316, 4 L. Ed. 579, where he noted that the Constitution is not a "splendid bauble" that states can abridge as they see fit. In 1821 he advanced the theory of judicial review, rejecting a challenge by the state of Virginia to the appellate authority of the Supreme Court (Cohens v. Virginia, 19 U.S. [6 Wheat.] 264, 5 L. Ed. 257). In his written opinions, Marshall typically relied on the power of logic and his own forceful eloquence, rather than citing law. This approach was noted by Associate Justice Joseph Story: "When I examine a question, I go from headland to headland, from case to case. Marshall has a compass, puts out to sea, and goes directly to the result." Marshall was not without opponents. Foremost among them was Jefferson. In 1810 Jefferson wrote to President James Madison that "[t]he Chief Justice's leadership was marked by "cunning and sophistry" and displayed "rancourous hatred" of the democratic principles of the Republicans. Jefferson led the Republican attack on Marshall with the accusation that he twisted the law to suit his own biases. Although Marshall weathered the attacks, his authority, and the Court's, was ultimately affected. Not all his decisions were enforced; some were openly resisted by the president. New appointments to the Court brought states' rights advocates onto the bench, and Marshall began to compromise as a leader and to make concessions to ideological opponents.

Marshall died in office on July 6, 1835.

"Listening well is as powerful a means of communication and influence as to talk well." "The power to tax is the power to destroy." "No political dreamer was ever wild enough to think of breaking down the lines which separate the States, and of compounding the American people into one common mass."

MARSHALL, John, (uncle of Thomas Francis Marshall and cousin of Humphrey Marshall [1760-1841]), a Representative from Virginia; born in Germantown, Fauquier County, Virginia, September 24, 1755; received instruction from a tutor and attended the classical academy of the Messrs. Campbell in Westmoreland County, Virginia; at the outbreak of the Revolutionary War joined a company of State militia that subsequently became part of the Eleventh Regiment of Virginia Troops; studied law at the College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, Virginia; was admitted to the bar on August 28, 1780; resigned his Army commission in 1781 and engaged in the practice of law in Fauquier County; delegate in the Virginia house of delegates in 1780; settled in Richmond and practiced law; member of the executive council 1782-1795; again a member of the house of burgesses 1782-1788; delegate to the State constitutional convention for the ratification of the Federal Constitution that met in Richmond June 2, 1788; one of the special commissioners to France in 1797 and 1798 to demand redress and reparation for hostile actions of that country; resumed the practice of law in Virginia; declined the appointment of Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States tendered by President Adams September 26, 1798; elected as a Federalist to the Sixth Congress and served from March 4, 1799, to June 7, 1800, when he resigned; was appointed Secretary of War by President Adams May 7, 1800, but the appointment was not considered, and on May 12, 1800, was appointed Secretary of State; entered upon his new duties June 6, 1800, and although appointed Chief Justice of the United States January 20, 1801, and notwithstanding he took the oath of office as Chief Justice February 4, 1801, continued to serve in the Cabinet until March 4, 1801; member of the Virginia convention of 1829; continued as Chief Justice until his death in Philadelphia, Pa., July 6, 1835; interment in the Shockoe Hill Cemetery, Richmond, Va. Extended Bibliography Beveridge, Albert J. John Marshall. Introduction by Henry Steele Commager. 1916-1919. Reprint, New York: Chelsea House, 1980. ---. The Life of John Marshall. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1916-1919. Reprint, Atlanta, Ga.: Cherokee Pub. Co., 1990. Brown, Richard Carl. John Marshall. Morristown, N.J.: Silver Burdett Co., [1968]. Corwin, Edward Samuel. John Marshall and the Constitution: A Chronicle of the Supreme Court. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1919. Reprint, Toronto: Glasgow, Brook; New York: U.S. Publishers Association, 1977. Craigmyle, Thomas Shaw, Baron. John Marshall in Diplomacy and in Law. New York: C. Scribner's Sons, 1933. Reprint, with an introduction by Nicholas Murray Butler. Buffalo, N.Y.: W.S. Hein & Co., 1995. Cuneo, John R. John Marshall, Judicial Statesman. New York: McGraw-Hill, [1975]. Faulkner, Robert K. The Jurisprudence of John Marshall. 1968. Reprint, Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1980. Feinberg, Barbara Silberdick. John Marshall: The Great Chief Justice. Springfield, N.J.: Enslow Publishers, 1995. Gunther, Gerald, comp. John Marshall's Defense of McCulloch v. Maryland. Edited and with an introduction. by Gerald Gunther. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1969. Haskins, George Lee. Foundations of Power: John Marshall, 1801-15. Part one by George Lee Haskins; part two by Herbert A. Johnson. New York : Macmillan Pub. Co., 1981. Hobson, Charles F. The Great Chief Justice: John Marshall and the Rule of Law. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1996. Johnson, Herbert Alan. The Chief Justiceship of John Marshall, 1801-1835. Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina Press, 1997. Jones, William Melville, ed. Chief Justice John Marshall; A Reappraisal. Ithaca, N.Y.: Published for College of William and Mary [by] Cornell University Press, [1956]. Reprint, New York: Da Capo Press, 1971. Kallen, Stuart A. John Marshall . Edina, Minn.: ABDO Pub., 2001. Loth, David Goldsmith. Chief Justice: John Marshall and the Growth of the Republic. New York: W. W. Norton, [1949]. Reprint, New York: Greenwood Press, [1970?]. Magruder, Allan B. (Allan Bowie). John Marshall. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1898. Reprint, New York: AMS Press, [1972]. Marshall, John. An Autobiograpical Sketch. Edited by John Stokes Adams. 1937. Reprint, New York: Da Capo Press, 1973. ---. The Constitutional Decisions of John Marshall. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1905. Reprint, Edited, with an introductory essay by Joseph P. Cotton, Jr. Union, N.J.: Lawbook Exchange, 2000. ---. George Washington. 1832. Reprint, New York: Chelsea House, 1981. ---. A history of the colonies planted by the English on the continent of North America, from their settlement to the commencement of that war which terminated in their independence. Philadelphia: A. Small, 1824. ---. John Marshall, complete constitutional decisions. Chicago: Callaghan & Company, 1903. ---. John Marshall, "A Friend of the Constitution": In defense and elaboration of McCulloch v. Maryland. Introduction: Unearthing John Marshall's major out-of-court constitutional commentary. By Gerald Gunther. [Stanford, Calif.: N.p., 1969]. ---. John Marshall, Complete Constitutional Decisions. Edited with annotations historical, critical, and legal by John M. Dillon. Chicago: Callaghan & Co., 1903. Reprint, Buffalo, N.Y.: W.S. Hein, 2003. ---. The Life of George Washington. Philadelphia: Printed and published by C. P. Wayne, 1805-07. Reprint, Edited by Robert Faulkner and Paul Carrese. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2000. ---. Major Opinions and Other Writings. Edited with an introduction and commentary by John P. Roche, with Stanley B. Bernstein. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, [1967]. ---. Opinions of the late Chief Justice of the United States (John Marshall) concerning freemasonry. [Boston?: N.p., 1840]. ---. The Papers of John Marshall. Edited by Herbert T. Johnson, Charles T. Cullen, Charles F. Hobson, and Nancy G. Harris. 7 vols. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1974. ---. The Political and Economic Doctrines of John Marshall, Who for Thirty-four years was Chief Justice of the United States. And also his letters, speeches, and hitherto unpublished and uncollected writings, by John Edward Oster. New York: The Neale Publishing Company, 1914. Reprint, New York: B. Franklin, [1967]. ---. Speech of the Hon. John Marshall, delivered in the House of Representatives of the United States, on the Resolutions of the Hon. Edward Livingston, relative to Thomas Nash, alias Jonathan Robbins. Philadelphia: Printed at the office of "The True American," 1800. ---. The Writings of John Marshall, Late Chief Justice of the United States, Upon the Federal Constitution. Boston: James Munroe and Company, 1839. Reprint, Littleton, Colo.: F.B. Rothman, 1987. Martini, Teri. John Marshall. Illustrated by Alex Stein. Philadelphia: Westminster Press, [1974]. Newmyer, R. Kent. The Supreme Court under Marshall and Taney. New York: Crowell, 1968. Reprint, Arlington Heights, Ill.: Harlan Davidson, [1986]. Richards, Gale L. "A Criticism of the Public Speaking of John Marshall Prior to 1801." Ph.D. diss., University of Iowa, 1951. Robarge, David Scott. A Chief Justice's Progress: John Marshall from Revolutionary Virginia to the Supreme Court. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 2000. Rudko, Frances Howell. John Marshall and International Law: Statesman and Chief Justice. New York: Greenwood Press, 1991. Shevory, Thomas C. John Marshall's Law: Interpretation, Ideology, and Interest. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1994. Siegel, Adrienne. The Marshall Court, 1801-1835. Millwood, N.Y.: Associated Faculty Press, 1987. Simon, James F. What Kind of Nation: Thomas Jefferson, John Marshall, and the Epic Struggle to Create a United States. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2002. Smith, Jean Edward. John Marshall: Definer of a Nation. New York: H. Holt & Co., 1996. Stites, Francis N. John Marshall, Defender of the Constitution. Edited by Oscar Handlin. Boston: Little, Brown, 1981. Turner, Kathryn. "The Appointment of Chief Justice Marshall." William and Mary Quarterly 3 ser. 17 (April 1960): 143-63. Wetterer, Charles M., and Margaret Wetterer Chief Justice. Illustrated by Kurt K.C. Walters. New York: Mondo Pub., 2005. White, G. Edward. The Marshall Court and Cultural Change, 1815-1835. With the aid of Gerald Gunther. New York: Macmillan Pub. Co., 1988. Reprint, New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

John Marshall (September 24, 1755 - July 6, 1835) was an American jurist and statesman who shaped American constitutional law and made the Supreme Court a center of power. Marshall was Chief Justice of the United States, serving from January 31, 1801, until his death in 1835. He served in the United States House of Representatives from March 4, 1799, to June 7, 1800, and was Secretary of State under President John Adams from June 6, 1800, to March 4, 1801. Marshall was from the Commonwealth of Virginia and a leader of the Federalist Party. The longest serving Chief Justice in Supreme Court history, Marshall dominated the Court for over three decades (a term outliving his own Federalist Party) and played a significant role in the development of the American legal system. Most notably, he established that the courts are entitled to exercise judicial review, the power to strike down laws that violate the Constitution. Thus, Marshall has been credited with cementing the position of the American judiciary as an independent and influential branch of government. Furthermore, the Marshall Court made several important decisions relating to federalism, shaping the balance of power between the federal government and the states during the early years of the republic. In particular, he repeatedly confirmed the supremacy of federal law over state law and supported an expansive reading of the enumerated powers. Early yearsJohn Marshall was born in a log cabin near Germantown, a rural community on the Virginia frontier, in what is now Fauquier County near Midland, Virginia, on September 24, 1755, to Thomas Marshall and Mary Randolph Keith. The oldest of fifteen, John had eight sisters and six brothers. Also, several cousins were raised with the family. From a young age, he was noted for his good humor and black eyes, which were "strong and penetrating, beaming with intelligence and good nature". Thomas Marshall was employed by Lord Fairfax. Known as "the Proprietor", Fairfax provided Thomas Marshall with a substantial income as his lordship's agent in Fauquier County. Marshall's task was to survey the tract, assist in finding people to settle and collect the modest rents. In the early 1760s, the Marshall family left Germantown and moved some thirty miles to Leeds Manor (so named by Lord Fairfax) on the eastern slope of the Blue Ridge. On the banks of Goose Creek, Thomas Marshall built a simple wooden cabin there, much like the one abandoned in Germantown with two rooms on the first floor and a two-room loft above. Thomas Marshall was not yet well estblished, so he leased it from Colonel Richard Henry Lee. The Marshalls called their new home "the Hollow", and the ten years they resided there were John Marshall's formative years. In 1773, the Marshall family moved once again. Thomas Marshall, by then a man of more substantial means, purchased a 1,700-acre estate adjacent to North Cobbler Mountain, approximately ten miles northwest of the Hollow. The new farm was located adjacent to the main stage road (now U.S. 17) between Salem (the modern day village of Marshall, Virginia) and Delaplane. When John was seventeen, Thomas Marshall built "Oak Hill" there, a seven-room frame home with four rooms on the first floor and three above. Although modest in comparison to the estates of Washington, Madison, and Jefferson, it was a substantial home for the period. John Marshall became the owner of Oak Hill in 1785 when his father moved to Kentucky. Although John Marshall lived his later life in Richmond and Washington, he kept his Fauquier County property, making improvements and using it as a retreat until his death. Marshall's early education was superintended by his father who gave him an early taste for history and poetry. Thomas Marshall's employer, Lord Fairfax, allowed access to his home at Greenway Court, which was an exceptional center of learning and culture. Marshall took advantage of the resources at Greenway Court and borrowed freely from the extensive collection of classical and contemporary literature. There were no schools in the region at the time, so home schooling was pursued. Although books were a rarity for most in the territory, Thomas Marshall's library was exceptional. His collection of literature, some of which was borrowed from Lord Fairfax, was relatively substantial and included works by Livy, Horace, Pope, Dryden, Milton, and Shakespeare. All of the Marshall children were accomplished, literate, and self-educated under their parents' supervision. At the age of twelve John had transcribed Alexander Pope's An Essay on Man and some of his Moral Essays. There being no formal school in Fauqueir County at the time, John was sent, at age fourteen, about one hundred miles from home to the academy of Reverend Archibald Campbell in Washington parish. Among his classmates was James Monroe. John remained at the academy one year, after which he was brought home. Afterwards, Thomas Marshall arranged with Edinbugh for a minister to be sent who could double as a teacher for the local children. The Reverend James Thomson, a recently ordained deacon from Glasgow, Scotland, resided with the Marshall family and tutored the children in Latin in return for his room and board. When Thomson left at the end of the year, John had begun reading and transcribing Horace and Livy. The Marshalls had long before decided that John was to be a lawyer. William Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England had been published in America and Thomas Marshall bought a copy for his own use and for John to read and study. After John returned home from Campbell's academy he continued his studies with no other aid than his Dictionary. John's father superintended the English part of his education. Marshall wrote of his father, "... and to his care I am indebted for anything valuable which I may have acquired in my youth. He was my only intelligent companion; and was both a watchful parent and an affectionate friend". Marshall served in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War and was friends with George Washington. He served first as a Lieutenant in the Culpeper Minute Men from 1775 to 1776, then as a Lieutenant in the Eleventh Virginia Continental Regiment from 1776 to 1780. During his time in the army, he enjoyed running races with the other soldiers and was nicknamed "Silverheels" for the white heels his mother had sewn into his stockings. After his time in the Army, he read law under the famous Chancellor George Wythe in Williamsburg, Virginia at the College of William and Mary was elected to Phi Beta Kappa and was admitted to the Bar in 1780. He was in private practice in Fauquier County, Virginia before entering politics. State political careerIn 1782, Marshall won a seat in the Virginia House of Delegates, in which he served until 1789 and again from 1795 to 1796. The Virginia General Assembly elected him to serve on the Council of State later in the same year. In 1785, Marshall took up the additional office of Recorder of the Richmond City Hustings Court. In 1788, Marshall was selected as a delegate to the Virginia convention responsible for ratifying or rejecting the United States Constitution, which had been proposed by the Philadelphia Convention a year earlier. Together with James Madison and Edmund Randolph, Marshall led the fight for ratification. He was especially active in defense of Article III, which provides for the Federal judiciary. His most prominent opponent at the ratification convention was Anti-Federalist leader Patrick Henry. Ultimately, the convention approved the Constitution by a vote of 89-79. Marshall identified with the new Federalist Party (which supported a strong national government and commercial interests), rather than Jefferson's Democratic-Republican Party (which advocated states' rights and idealized the yeoman farmer and the >French Revolution). Biography of WashingtonMarshall greatly admired George Washington, and wrote a highly influential biography. Between 1805 and 1807, he published a five-volume biography; his Life of Washington was based on records and papers provided him by the president's family. The first volume was reissued in 1824 separately as A History of the American Colonies. The work reflected Marshall's Federalist principles. His revised and condensed two-volume Life of Washington was published in 1832. Vol 1. Vol 2. Historians have often praised its accuracy and well-reasoned judgments, while noting his frequent paraphrases of published sources such as William Gordon's 1801 history of the Revolution and the British Annual Register. After completing the revision to his biography of Washington, Marshall prepared an abridgment. In 1833 he wrote, "I have at length completed an abridgment of the Life of Washington for the use of schools. I have endeavored to compress it as much as possible. . . . After striking out every thing which in my judgment could be properly excluded the volume will contain at least 400 pages." Cary & Lea did publish the abridgment, but only in 1838, three years after Marshall died. Chief JusticeIn 1801, during the last weeks of his term as president, Adams appointed several federal judges (the "Midnight Judges"), including Marshall as Chief Justice of the United States on January 20, 1801. One week later, the Senate confirmed his nomination unanimously, and Marshall received his commission on February 4. The three previous chief justices (John Jay, John Rutledge, and Oliver Ellsworth) had left little permanent mark beyond setting up the forms of office. The Supreme Court, like the state supreme courts, was a minor organ of government. In his 34-year tenure, Marshall made it a third co-equal branch, which it remains today. With his associate justices, especially Joseph Story, William Johnson, and Bushrod Washington, Marshall's Court defined the constitutional standards of the new nation. The great work of the Marshall Court was done in a handful of great cases, especially Marbury v. Madison, McCulloch v. Maryland, Cohens v. Virginia and Gibbons v. Ogden. His influential rulings reshaped American government, revealing the Supreme Court as the final arbiter of the Constitution-a document with respect to which the Court has the power to overrule the Congress, the president, the states, and all lower courts. He fought to protect the rights of individuals and corporations against intrusive state governments. Marshall, along with Daniel Webster (who argued some of the cases), was the leading Federalist of the day, pursuing Federalist approaches to build a stronger federal government over the opposition of Thomas Jefferson and the Democratic-Republicans, who wanted stronger state governments. Marshall's most important rulings include Cohens v. Virginia, Fletcher v. Peck, Gibbons v. Ogden, Marbury v. Madison, McCulloch v. Maryland, Trustees of Dartmouth College v. Woodward, and Worcester v. Georgia. Some of his decisions were unpopular; Andrew Jackson went so far as to completely ignore the ruling of Worcester v. Georgia, for example. Nevertheless, Marshall set a great precedent in American politics by being able to balance out the branches of government, and the states and the federal power, providing the rule of law that still prevails. One of Marshall's most lasting contributions to the Supreme Court was in how opinions are delivered. Before Marshall, opinions were delivered seriatim, meaning each justice delivered a separate opinion. That model is still used by the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom. However, Marshall convinced his colleagues to adopt a single opinion for the court, allowing it to present a clear rule. During his 34 years as Chief Justice he judged over 1,100 cases; he wrote the majority opinion in 519. Marshall was in the dissenting minority only eight times throughout his tenure at the court because of his control over the associate justices. As one observer at the time noted, Marshall had the knack of "putting his own ideas into the minds of others, unconsciously to them". Marshall had charm, humor, a quick intelligence, and the ability to bring men together. Above all, he had patriotism, sincerity and presence that commanded attention. His opinions were workmanlike, not eloquent in style or subtle; and his learning in the law was not deep. What distinguished him was the force of his intellect, steadfast purpose, and a confident vision of the future greatness he wanted his nation to achieve; these qualities are seen in his historic decisions and gave him the sobriquet, The Great Chief Justice. Marbury v. MadisonMarbury v. Madison, decided in 1803, ruled for the government (that is, Madison), by deciding a minor law passed by Congress was unconstitutional. Ironically what was unconstitutional was Congress' granting a certain power to the Supreme Court itself. The case allowed Marshall to proclaim the doctrine of judicial review, which reserves to the Supreme Court final authority to judge whether or not actions of the president or of the Congress are within the powers granted to them by the Constitution. The Constitution itself is the supreme law, and when the Court believes that a specific law or action is in violation of it, the Court must uphold the Constitution and set aside that other law or action. The Constitution does not explicitly give judicial review to the Court, and Jefferson was very angry with Marshall's position, for he wanted the president to decide whether his acts were constitutional or not. Historians mostly agree that the Founding Fathers Constitution did plan for the Supreme Court to have some sort of judicial review; what Marshall did was make operational their goals. Judicial review was not new and Marshall himself mentioned it in the Virginia ratifying convention of 1788. Marshall's opinion expressed and fixed in the American tradition and legal system a more basic theory-government under law. That is, judicial review means a government in which no person (not even the president) and no institution (not even Congress), nor even a majority of voters, may freely work their will in violation of the written Constitution. Marshall himself never declared another act of Congress or of a president unconstitutional. McCulloch v. MarylandMcCulloch v. Maryland, (1819) was Marshall's greatest single judicial performance. While it was consistent with Marbury v. Madison, it cuts the other way and prevents states from passing laws that violate the national Constitution. The heart of this opinion is the famous statement, "We must never forget that it is a constitution we are expounding." Marshall laid down the basic theory of implied powers under a written Constitution; a written, but a living, Constitution, intended, as he said "to endure for ages to come, and, consequently, to be adapted to the various crises of human affairs ... ." Marshall envisaged a federal government which, although governed by timeless principles, possessed the plenary powers "on which the welfare of a nation essentially depends." It would be free in its choice of means, not tied to a literal interpretation of the Constitution, and open to change and growth. Cohens v. VirginiaCohens v. Virginia (1821) displayed Marshall's nationalism as he enforced the supremacy of federal law over conflicting state law and overturned the Virginia supreme court. The decision means the federal judiciary can act directly on private parties and state officials, and has the power to declare and impose on the states the Constitution and federal laws. Gibbons v. OgdenGibbons v. Ogden (1824) overturned a monopoly granted by the New York state legislature to certain steamships operating between New York and New Jersey. In empowering Congress to regulate interstate commerce, the Constitution automatically deprived the states of the power to obstruct interstate commerce in order to serve their own interests. The long-term impact was ending many state-granted monopolies and promoting free enterprise. Other work, later life, legacyMarshall loved his home, built in 1790, in Richmond, Virginia, and spent as much time there as possible in quiet contentment. While in Richmond he attended St. John's Church in Church Hill until 1814 when he led the movement to hire Robert Mills as architect of Monumental Church, which commemorated the death of 72 Virginians. The Marshall family occupied pew No. 23 at Monumental Church and entertained the Marquis de Lafayette there during his visit to Richmond in 1824. For approximately three months each year, however, he would be away in Washington for the Court's annual term; he would also be away for several weeks to serve on the circuit court in Raleigh, North Carolina. In 1823, he became first president of the Richmond branch of the American Colonization Society, which was dedicated to resettling freed American slaves in Liberia, on the West coast of Africa. In 1828, he presided over a convention to promote internal improvements in Virginia. In 1829, he was a delegate to the state constitutional convention, where he was again joined by fellow American statesman and loyal Virginians, James Madison and James Monroe, although all were quite old by that time. Marshall mainly spoke at this convention to promote the necessity of an independent judiciary. On December 25, 1831, Mary, his beloved wife of some 49 years, died. Most who knew Marshall agreed that after Mary's death, he was never quite the same. On returning from Washington in the spring of 1835, he suffered severe contusions resulting from an accident to the stage coach in which he was riding. His health, which had not been good for several years, now rapidly declined, and in June he journeyed to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania for medical attendance. There he died on July 6, at the age of 79, having served as Chief Justice for over 34 years. He also was the last surviving member of John Adams's Cabinet and the second to last surviving Founding Father, the last being James Madison. Two days before his death, he enjoined his friends to place only a plain slab over his and his wife's graves, and he wrote the simple inscription himself. His body, which was taken to Richmond, lies in Shockoe Hill Cemetery in a well kept grave. JOHN MARSHALL Monuments and memorials

Marshall Memorial (1883, William Wetmore Story) in John Marshall Park, Washington, D.C.

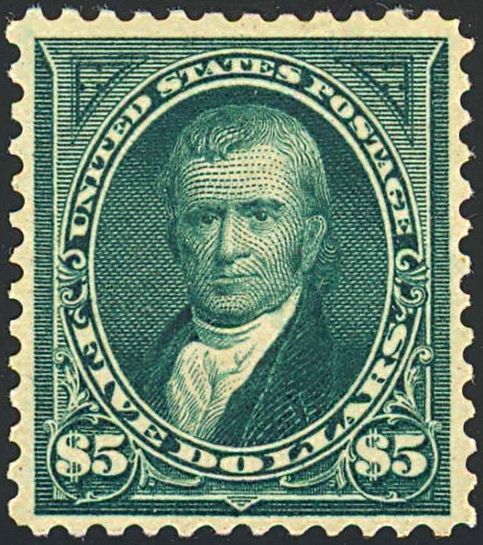

Marshall's home in Richmond, Virginia, has been preserved by APVA Preservation Virginia. It is considered to be an important landmark and museum, essential to an understanding of the Chief Justice's life and work. The United States Bar Association commissioned sculptor William Wetmore Story to execute the statue of Marshall that now stands inside the Supreme Court on the ground floor. Another casting of the statue is located at Constitution Ave. and 4th Street in Washington D.C. and a third on the grounds of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Story's father Joseph Story had served as an Associate Justice on the United States Supreme Court with Marshall. The statue was originally dedicated in 1884. An engraved portrait of Marshall appears on U.S. paper money on the series 1890 and 1891 treasury notes. These rare notes are in great demand by note collectors today. Also, in 1914, an engraved portrait of Marshall was used as the central vignette on series 1914 $500 federal reserve notes. These notes are also quite scarce. Example of both notes are available for viewing on the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco website. On September 24, 1955, the United States Postal Service issued the 40’ Liberty Issue postage stamp honoring Marshall with a 40 cent stamp. Having grown from a Reformed Church academy, Marshall College, named upon the death of Chief Justice John Marshall, officially opened in 1836 with a well-established reputation. After a merger with Franklin College in 1853, the school was renamed Franklin and Marshall College. The college went on to become one of the nation's foremost liberal arts colleges. Four law schools and one University today bear his name: The Marshall-Wythe School of Law (now William and Mary Law School at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia; The Cleveland-Marshall College of Law in Cleveland, Ohio; John Marshall Law School in Atlanta, Georgia; and, The John Marshall Law School in Chicago, Illinois. The University that bears his name is Marshall University in Huntington West Virginia. Marshall County, Illinois, Marshall County, Indiana, Marshall County, Kentucky and Marshall County, West Virginia are also named in his honor. A number of high schools around the nation have also been named for him. John Marshall's birthplace in Fauquier County is a park, the John Marshall Birthplace Park, and a marker can be seen on Route 28 noting this place and event. The village of Marshall, Virginia is named after John Marshall. Marshall, Michigan was named by town founders Sidney and George Ketchum in honor of the Chief Justice of the United States John Marshall from Virginia-whom they greatly admired. Occurring five years before Marshall's death, it was the first of dozens of communities and counties named for him. Marshalltown, Iowa was allegedly named for the Michigan city, but adopted its current name because there was already a Marshall, Iowa John Marshall was an active Freemason and served as Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of Ancient Free and Accepted Masons of the Commonwealth of Virginia. Prominent family connections

Bibliography

Primary sources

Further reading

Notes

See alsoReferences

External links

This entry is from Wikipedia, the leading user-contributed encyclopedia. It may not have been reviewed by professional editors (see full disclaimer) Related topics:

Related answers:

Help us answer these:

Copyrights:

Mentioned in

» More» More

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

John Marshall Community

High School

10101 E 38th Street

Indianapolis, Indiana

46235-1999

(317) 693-5460